As the historical gathering of Water Protectors blocking the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation continues, people from all around the world are seeing the legacy of colonialism and environmental racism play out before their eyes. We know that the systems of control and extraction that cause environmental degradation, climate change, and the gulf in our relationship to the earth and one another are playing out at Standing Rock. With fears about what the new administration could mean for tribal sovereignty and water rights, each of us is called to discern how we are to be healing forces in the face of these events. How do we recover from this: oil companies forcing indigenous residents to accept the destruction of burial sites, the confiscation of eagle feathers and prayer pipes, young men on horses shot with rubber bullets, their horses tazed and dropping to the ground dead?

As the historical gathering of Water Protectors blocking the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation continues, people from all around the world are seeing the legacy of colonialism and environmental racism play out before their eyes. We know that the systems of control and extraction that cause environmental degradation, climate change, and the gulf in our relationship to the earth and one another are playing out at Standing Rock. With fears about what the new administration could mean for tribal sovereignty and water rights, each of us is called to discern how we are to be healing forces in the face of these events. How do we recover from this: oil companies forcing indigenous residents to accept the destruction of burial sites, the confiscation of eagle feathers and prayer pipes, young men on horses shot with rubber bullets, their horses tazed and dropping to the ground dead?

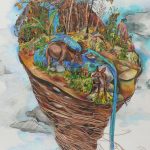

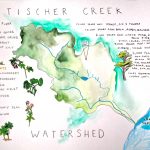

Ched Myers started me on a journey last spring of exploring the ways settler people like myself can begin the healing work of decolonizing in our own watersheds. It is this experience on which I have chosen to base my internship with EcoFaith Recovery. I am grateful for the mentorship and guidance Ched and the leaders at EcoFaith Recovery have provided me as I discern ordination with the Roman Catholic Womenpriests. As I think about new, inclusive models of priesthood and a church re-imagined in light of our current reality, I have come to believe that healing starts with learning the story of the land on which we reside. In a short amount of time, I plan to start “Muddy Water Garden Church” here in the Tischer Creek Watershed of Duluth, MN. I dream that this will be an eco-feminist, sacramental, community of Watershed Discipleship. This will be a community that lifts up the voices of the survivors of all kinds of trauma (with an emphasis on gendered violence), a community that awakens leaders, healers, and organizers. I long for a space where we will together follow new paths of recovery. This will all happen within the context of the garden.

What exactly does it look like to be building sacred community on land that was stolen, land on which I play the role of white settler and colonizer? What are the practical steps settler people might make to co-create within the story of the land and its original inhabitants and historical caretakers (plant, animal, and human) rather than coming in and enforcing our dreams upon it (again)? How do we contribute to the land’s healing from its history of settlement and manipulation rather than contributing to that trauma?

With Ched’s guidance, I committed to a season of exploration, study, observation and listening (yes, this falls under the Rhythms of Engagement). Ched’s idea of a three-fold process of Radically Responsible Settler Gardening Practices has set the stage for Garden Church to be a place that fosters what Syed Hussan calls, “a dramatic re-imagining of relationships with land, people and the state [that] requires study, requires conversation, it is a practice, it is an unlearning.” During this time, I have been: learning the botanical and natural history of the particular plot of land (how did this land look before colonization?), finding out what the history of settlement on this land has looked like (and felt like—what trauma has the land endured?), and asking how I can best co-create with this place in a way which reconciles ecological processes with my own community needs. A research year at the beginning of the time with this space new to me insures that as I begin Garden Church, it will be done with a working knowledge of these three layers: history, trauma, and co-creation.

1. Soil: Story

Local Ojibwe elder Babette Sandman frequently talks about blood memory. The same way an Ojibwa-ikway (an Ojibwe/Anishinaabe woman) might have dreams of Lake Superior after growing up on a reservation in South Dakota without ever having seen the big lake with her waking eyes, the memory of what it means to dominate and colonize is alive in settler blood. Without knowing it, settler folk might repeat the damaging actions of our ancestors. The forces of extraction capitalism push us away and distract us from connecting to our stories, so the work of radically responsible gardening practices necessarily starts at a point of reconnection. Honoring that we do not live on un-storied place means that we must accept that we are not un-storied people. The work of unearthing our own immigration and ancestral history necessarily goes hand in hand with interacting with the stories of the land we live on.

Local Ojibwe elder Babette Sandman frequently talks about blood memory. The same way an Ojibwa-ikway (an Ojibwe/Anishinaabe woman) might have dreams of Lake Superior after growing up on a reservation in South Dakota without ever having seen the big lake with her waking eyes, the memory of what it means to dominate and colonize is alive in settler blood. Without knowing it, settler folk might repeat the damaging actions of our ancestors. The forces of extraction capitalism push us away and distract us from connecting to our stories, so the work of radically responsible gardening practices necessarily starts at a point of reconnection. Honoring that we do not live on un-storied place means that we must accept that we are not un-storied people. The work of unearthing our own immigration and ancestral history necessarily goes hand in hand with interacting with the stories of the land we live on.

The path to re-inhabiting a suburban space begins with deliberately digging into the deep history of place. The particular goal of this first layer of research is to find out what the land looked like before colonization. Steps might include (but are not exclusive to):

- researching the natural history of the watershed

- learning about and from the indigenous people that were and are the traditional caretakers

- exploring the languages of those original peoples (the words and sound native to the air)

- learning the names and ethnobotanies of the plants (making an exercise of introducing oneself to a new plant every week)

- looking into what native peoples did to manage the wilderness

- finding out the history of fauna (What used to live here in abundance? What has gone extinct?)

- completing the Big Here exercise.

In upcoming blog posts, I will share how some of that preliminary work has looked for me on the land with which I am journeying.

2. Roots: Historical Trauma

W hen Nathan and I moved into our house, we invited local indigenous (Ojibwe/Anishinaabe) elders Skip and Babette Sandman over to dinner. We knew Skip and Babette from doing work in the community and we wanted to share a meal and ask them a question we had seen modeled by Randy and Edith Woodley on Eloheh Farm near Newberg, Oregon. Randy (Cherokee) and Edith (Shoshone) run a regenerative farm that doubles as a community school that teaches permaculture, bio-mimicry and traditional indigenous knowledge. Although both Randy and Edith are indigenous, they are not indigenous to the land they have settled on near Newberg. Randy tells the story of how when they bought the piece of land that they now live and work on, he reached out to elders of the Kalapuya tribe to ask the question, “How do you want us to use this land that is your land?” The response that Randy got was to plant huckleberry bushes. Instead of the traditional gift of tobacco, Randy and Edith now ask visitors to the farm to bring an elderberry bush to honor the Kalapuya people.

hen Nathan and I moved into our house, we invited local indigenous (Ojibwe/Anishinaabe) elders Skip and Babette Sandman over to dinner. We knew Skip and Babette from doing work in the community and we wanted to share a meal and ask them a question we had seen modeled by Randy and Edith Woodley on Eloheh Farm near Newberg, Oregon. Randy (Cherokee) and Edith (Shoshone) run a regenerative farm that doubles as a community school that teaches permaculture, bio-mimicry and traditional indigenous knowledge. Although both Randy and Edith are indigenous, they are not indigenous to the land they have settled on near Newberg. Randy tells the story of how when they bought the piece of land that they now live and work on, he reached out to elders of the Kalapuya tribe to ask the question, “How do you want us to use this land that is your land?” The response that Randy got was to plant huckleberry bushes. Instead of the traditional gift of tobacco, Randy and Edith now ask visitors to the farm to bring an elderberry bush to honor the Kalapuya people.

Nathan and I were expecting to get a similar answer from Skip and Babette when we asked them if they had guidance in how we should relate to the land that our house is on. What we got was something very different. Skip told us to always ask the land, “What do you need to be healed?” Babette imagined a day when people could come to our yard and hold the earth in their hands and hear a story of what the soil had gone through, how it was ancient and filled with memory and resilience. They both wondered if our house and yard could be a spot on the developing Duluth Sacred Sites tour: maybe folks could stop and hear how we were relating to the land as settler people and share the story in that way.

This has been the most incredible part of this journey for me, for it was not long after I began learning the history of settlement of the Tischer Creek Watershed that I began to see the world with new eyes. I wondered what the red pines in my backyard had seen. My daily walks in the woods were transformed. As I began to be in relationship with the story of the soil and trees that surrounded me, my own story of healing began to be drawn out. My spiritual director suggested that I engage my own story on the same level as I was engaging the story of the land. This has led me to find mentors, co-healers and imaginers as I do this work. It has allowed me to see my wounds as power. I am becoming more human by engaging the story of myself in relationship to this place.

3. Stalks and Leaves: Design and Co-Creation

Ideally, radically responsible settlers would go through a whole annual season watching the rhythms of a space. Where does the sun hit the most? How does the water pool? What is already growing? How does this compare to wild areas nearby (if there are any)? As the layers of research come together, a sensory relationship can be formed with the land as well. I have spent a lot of time in my yard simply feeling the space. I have engaged in relationship with the land through prayer, through art, and through song at all times of day. Slowly, a relationship has developed that will inform how and what I will plant here.

Through the integration of all three layers of inquiry, a more mindful approach to re-inhabitation forms. Healing the land can only come from knowing its story, and it takes time to learn and understand. In fact, it takes much longer than a research year. (And much of it can only be learned by actively experimenting with gentle but courageous hands in the soil.) I look forward to continuing to share the fruit from my foray into the land of radically responsible research and hope that it can inspire others to do this work where they live. The stories want to be told, and those who seek shall find.

Taking a cue from the natural world and going deeply into a season of profound listening, opening our senses, and relearning the land is countercultural to the capitalist system of constant output, but it is one that will serve us, and our sacred gardens, well over the long journey of placed-ness. What awaits is an encounter with manna (truly, there is enough for everyone!), gained confidence and competence with how the world provides for and heals us (if we are willing to do healing work alongside of her), and tools to imagine and grow creative, local, sustainable economies in our own back and front yards.

All artworks in this blog are originals by Sarah Holst.

Further Reading

Accomplices Not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex

www.indigenousaction.org

Taking Sides: Revolutionary Solidarity and the Poverty of Liberalism

edited by Cindy Milstein

Trauma and Memory: Challenges to Settler Solidarity

Elaine Enns

Soil & Sacrament TED Talk

Fred Bahnson

________________________________________________________

To sign up to receive these blog post directly to your email account, click here or on the link in the upper right sidebar of any page at ecofaithrecovery.org.

Please feel free to share this post with others and use the field below to post your thoughts on this topic. Thanks!